I often find that keeping up with the ongoings of the world and its inhabitants is ‘unsavory’ to put it in its less eloquent form, but ‘fucking horrific’ would be more true to my own vernacular.

People are shit, everything is slowly dying, and information is skewed to induce a constant state of paranoia to those it reaches. There is some sort of massive feedback loop that exists to keep everything within a constant state of misery, but its circumference is likely way too vast for us to even understand that we have found ourselves within it. Our brains were not engineered to psychologically be able to withstand the brunt of worldly suffering - to have to bear witness to tragedy, war, injustice - genocide.

It doesn’t really matter how we’ve arrived at this state of existence now, but its interesting how the human psyche still attempts to adapt to it.

After understanding the unsavory-ness of the world, how do you react? Do you protest? Do you support the ideal politician? Do you attempt to minimize your own, individual ecological footprint?

Or, do you shield your eyes from it all - keeping your head low, finding safe pockets of escapism that are scattered between the facets of you and everyone else’s life that you’d rather not acknowledge, because such things are inconvenient? (I wonder how many rhetorical questions I should include here to get my point across?)

This is not meant to carry a wholly nihilistic demeanor - all of these ways of coping with reality are valid in their own way. For someone to have an awareness of all of these things and still choose to continue living is a feat that we should give ourselves credit for more often.

We have no easy solutions to any problems - most are far too complicated to ever be resolved within our lifetime, and their answers will often require the suffering of others, simply displacing that same negative energy instead of ridding ourselves of it.

Life is a series of infinitesimal vibrations. Vibrations that reverberate from ourselves onto the things around us. Onto other living things with their own vibrations. Sometimes they are capable of approaching what seems like harmony, but in most instances, they differ vastly in their tunes, clashing to create these tiny, discordant juxtapositions that become unpleasant to the proverbial ear.

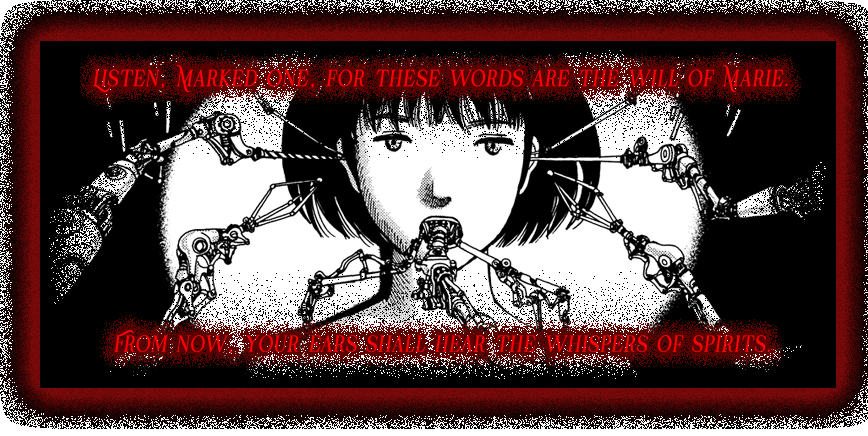

For the people of Piril, these vibrations are tuned to be resonant by their god, Marie, as she hovers above the world, maintaining the synchronicity of the human orchestra.

“The Music of Marie” (Marie no Kanaderu Ongaku) was written by mangaka 古屋兎丸 (Usamaru Furuya) and was originally published in 1999, having only recently been given an official English translation in 2022 (wow!) by One Peace Books. The story takes place over sixteen chapters, split between two tankobon volumes.

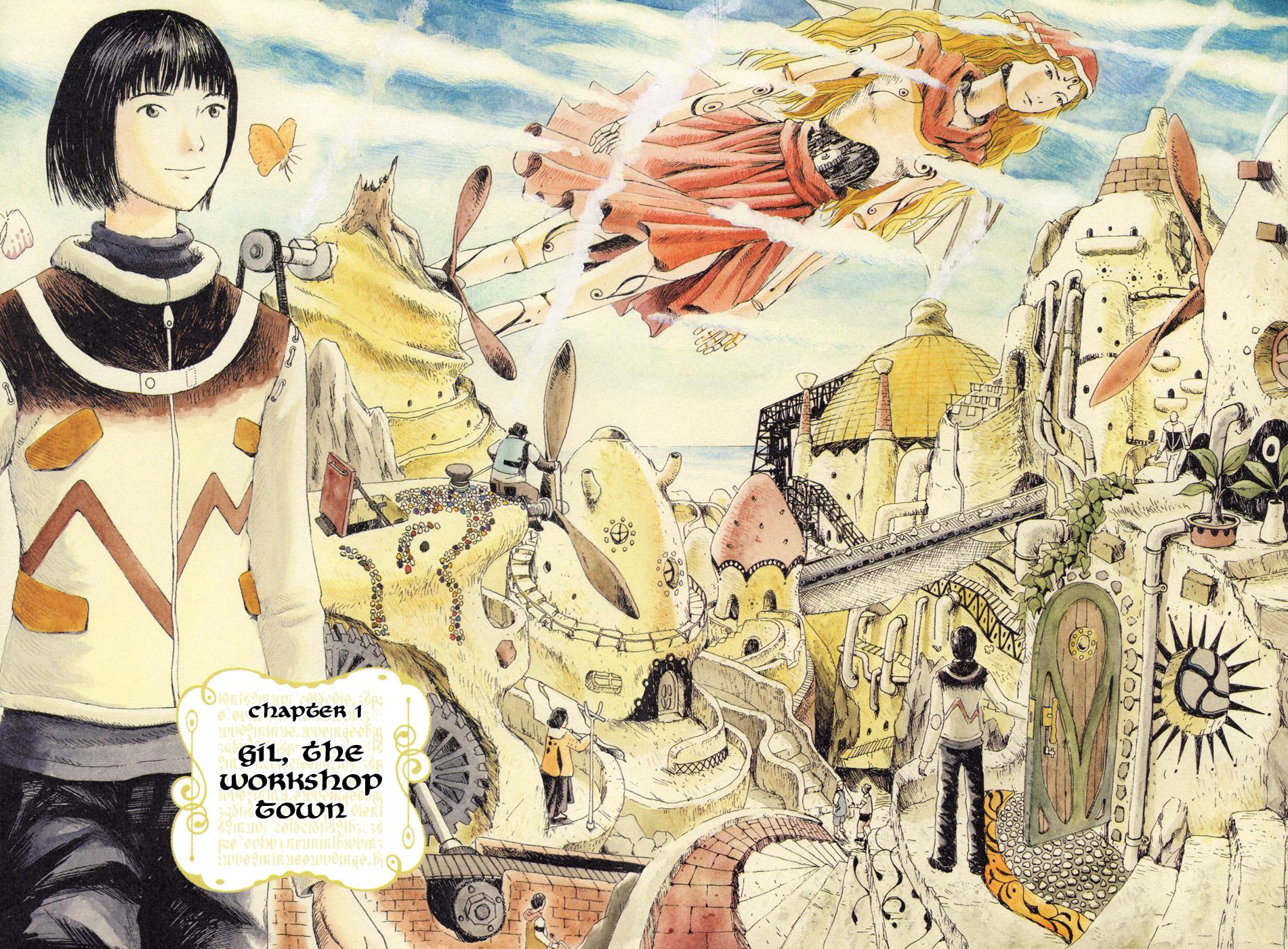

The story primarily follows characters Kai and Pipi as they go about their lives on a fictional island in a world that parallels the real-life Earth. This particular town is known for its advanced technology, with the inhabitants all seemingly working together to create these impressive feats of engineering - Pipi’s dad creates fantastic clockwork-like animals that move on their own around their garden. The setting illustrates this place in almost a whimsical, dreamlike existence for the islanders, and, indeed, the tone is very optimistic towards how their society operates.

I want to also mention how GORGEOUS the artwork is. Many of the panels feature incredibly detailed landscapes, where the linework dances in small colonies of swirls that create the presence of a pleasant breeze or encompass the rolling hills of the landscape. This is beautifully juxtaposed with the machines shown underground and inside shops and factories that are drawn dark, rigid, and in extreme detail, almost as if to parallel the blissful simplicity of the natural world with the brutal calculation of man-made mechanisms.

I am not familiar with this mangaka’s work, but “The Music of Marie” specifically features some incredibly-detailed depictions of a fantasy world that could have existed if the nature of civilization weren’t so tumultuous.

Pipi, who is quickly approaching a sort of matchmaking ceremony on the day of her 18th birthday, has secretly loved Kai since they were children. However, the more she looks into his eyes, the more she realizes he is not exchanging glances back. It seems as if his gaze is always affixed onto something elsewhere - specifically, onto the colossal deity known as “Marie” that hovers above the entire world, gently swaying constantly over every living thing from the sky.

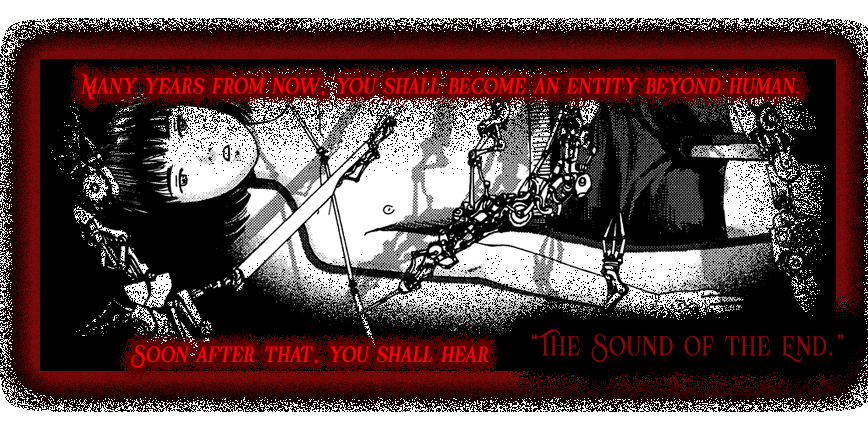

Whereas normal people cannot see Marie, Kai was mysteriously “chosen” as a child to be able to sense Marie - to see her massive, celestial body as she looks down on their town, and more importantly - to hear that sound of which she emits at all times. A song that keeps the temperaments of society in tune, that serves to quell the unrest that bubbles up naturally from within people.

The “melody” of Marie keeps humanity in a state of civility. People act within reason - arguments are solved peacefully, and compromise is always an option between two opposing parties. As a result, tragedy is minimized - the world generally lives in peace with each other.

It is explained that several holidays revolve around the various cities across Piril exchanging goods with each other out of mutual benefit, and there is even a somewhat touching section of the story where the main cast goes on a pilgrimage in praise of their goddess. During which, we see many of the other nations join them, and despite their many different languages and forms of praise, they are all rather respectful amongst themselves, and the diversity of peoples and cultures is celebrated.

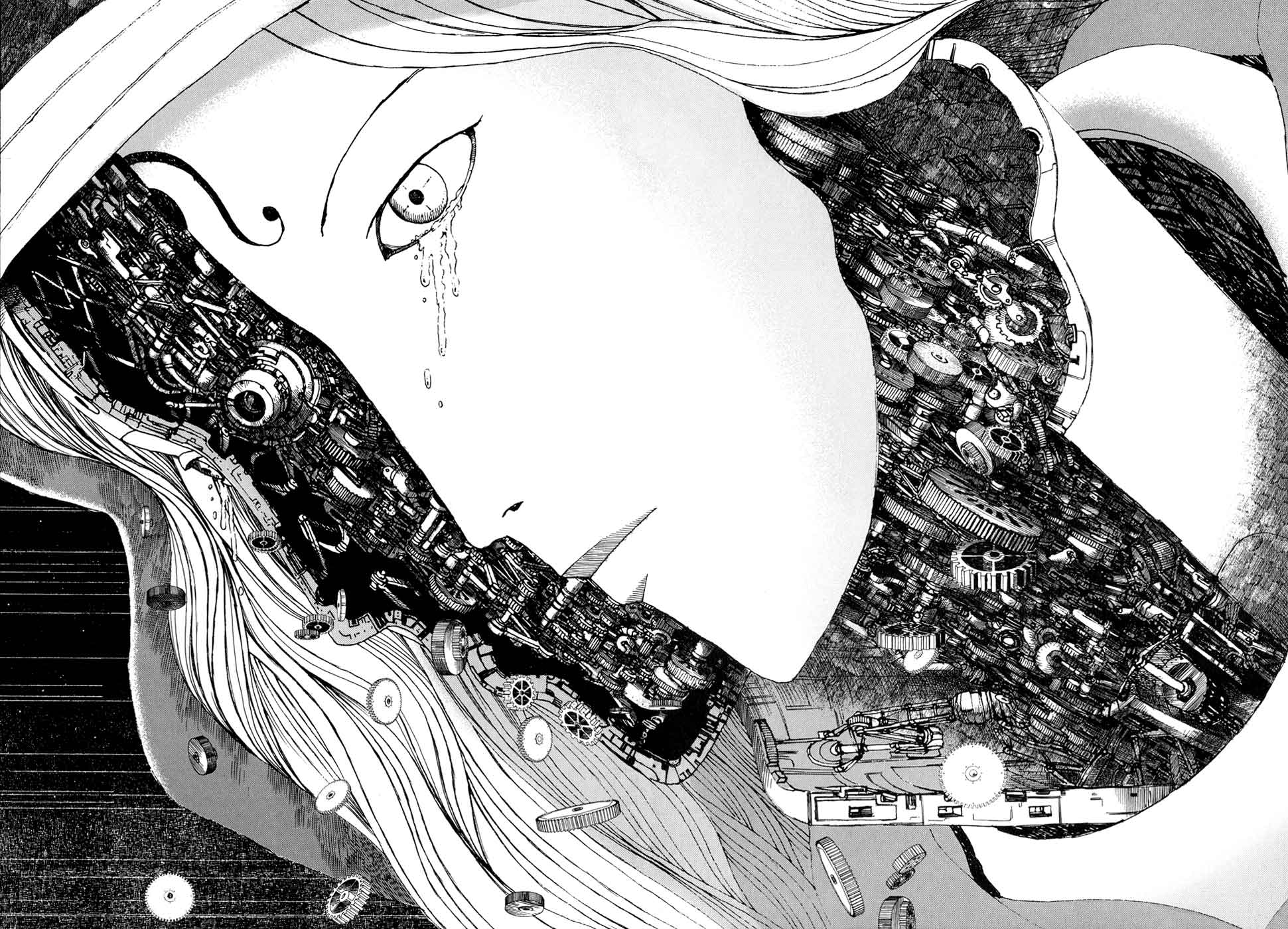

Though, there is a rather large paradox within the relationship between humans and their supreme goddess Marie. We are fed bits of context surrounding how technological progression seems to always halt right before massive breakthroughs - how the technology of their ancestors seem like they should work - in theory - but simply refuse to, almost as if they are defying the logic of science. We see this is especially evident when Pipi’s dad creates a “flying machine”, as when it is put to use, its circuitry seems to explode without reason.

This too, would be explained by the clairvoyant Kai to also have been the work of Marie; for when the machine takes flight, Marie begins to sing a different melody: a cacophony of abrasive noise. A dissonant piece that spells destruction, from which we come to understand the ambivalent nature of this world’s creator.

But is that really happiness?"

“Marie” is, in actuality, the most imposing creation that civilization has ever conceived: a tool that prevents technology from progressing to a stage in which it deems the beginning of global suffering (which according to the author, seems to begin around the age of flight, and the development of computation devices that ever-so-slightly exceed calculators). It would seem that at some point, humans decided that the best way to avoid a dystopian future was to construct a deity that would brute-force the population into a form of complacency in which adversity could never even possibly manifest. A form of complacency that keeps humanity in a paradox, where the order of the world accels the development of technology, yet creates a ceiling such that it may never expand upwards.

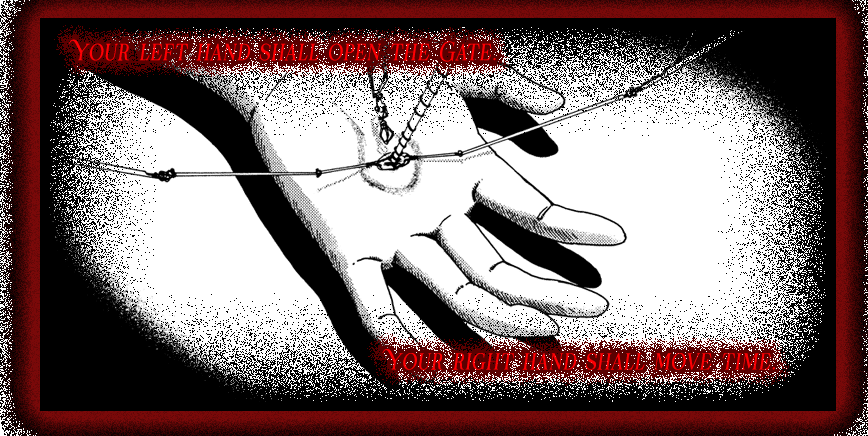

The last event during the story that is worth mentioning is a scene where Marie’s “music” comes to an abrupt stop. Kai is led inside of Marie, where he finds a massive music box which is revealed to be the source of her divine powers.

The massive contraption needs to be manually restarted every fifty years so that it can continue playing its tune. Whether or not this was a design choice that was implemented by her architects as a means of granting their descendants the option of free-will, or if it is just the eventual limitation of Marie’s dominion - is not known (or left vague intentionally).

Kai’s abilities are the result of him being chosen - a single representative for the current iteration of humanity, who is to decide whether or not humanity should continue on the same course of technological bottlenecking by restarting the music box, or to break the cycle, abandon the presence of Marie by leaving the music box unplayed, and face the reintroduction of war, genocide, and suffering into the world.

Without going into much detail, we are shown both possible futures. When Kai refuses to restart the melody - having seen its grip that it has over the progress of the world - he (and us readers) are shown horrific scenes. Scenes in which the main cast - once innocently exploring various parts of the town in seeming carefreeness, are portrayed as victims of a life that no longer grants opportunity for simple reprieve. They suffer - they starve - they fight. They spiral into despair. The mangaka holds little back in demonstrating the bleakness of this future.

The outcome as to whether or not Kai ultimately decides to further humanity’s compliance or to further the progression of time is not nearly as significant as the fact that he was even granted two possibilities in the first place.

I do not believe in God.

I was raised to be of Christian faith, but that no longer subsists in my general rotation of worldly concerns. I don’t care to argue for or against my view on faith or the faith of others. One could classify me as agnostic, but even to that extent, I hardly care enough about my own views enough to defend such fence-sitting to others.

However, what I am interested in is how faith can affect our thought processes. How this tool called “religion” has brought us into our current state. While it is possible you can attribute differing systems of beliefs centralized around fictional deities to historically be the crux of a multitude of human conflicts, I do not want to approach the subject with that kind of basic pessimism.

Religion is the means in which we have, and continue to, regulate ourselves. Suffering has always existed throughout life, and theism is the most accessible way to reach a semblance of reprieve from it.

I have always found “faith” to be a powerful word. Because, to imply that one has faith is to say that they can put their beliefs into places that they can never know truly exists or not - places from which they may never know if their dedication to such “faith” will ever yield any sort of return. Faith is one of the bravest things a human can ever decide to have - religious in nature, or not, because it is - by definition - an irrational act.

And what drives humans to develop “faith”? One could inherit it from their family unit, or had been indoctrinated into a faith by some sort means. But I'm trying to consider this answer from a more global perspective, because I believe that the root cause of faith is the presence of tragedy.

It’s possible that I'm twisting my own thoughts into a sort of ouroboros, because if we cling to faith to save ourselves from tragedy, and yet faith has caused even more tragedy, where do we escape the cycle? (I’m wondering if this beast is the same feedback loop I mentioned prior??)

I feel like maybe I'm spiraling a bit, so my point (I think?) is that “The Music of Marie” presents us with the question of whether or not we are willing to abandon the concept of “faith” and accept a reality full-force that we might have trouble coping with.

However, it does this in an interesting way, because it acknowledges that “faith” has a valid existence as well. It might be easy for us to have this discussion and conclude “well, I believe that we should pursue reality, despite how bleak it may be”, but that is would be kinda ignorant of us, as we then proceed to play video games for twelve hours, and talk about whatever topical media we can use to construct a stringent communication with others, as we safely tow some light conjecture into each other’s general directions. So as to not derive the topic into a discussion on how digital media has affected our psyche (which is the crux of most anything poignant I ever have to say honestly), let’s just conclude that people will always resort to escapism when it is needed. Perhaps “faith” is one flavor of many varieties of this.

The story shows us that clinging to the divine has its own merits, much like how it does in our own, not as well-drawn reality. Does faith help you maintain your compassion for people, despite the presence of homicide and rape? Might it grant its followers opportunities to be charitable, or to be selfless. If faith can drive someone to find the best version of themself, how ignorant is it, in actuality?

As previously mentioned secularite(?), I do not believe that I have reached a superior state of living than those that abide by religious practice. Maybe at one point I did, many stages of frontal-lobe development ago, but a more accurate way to perceive myself is actually lower than those of piety, most likely. In reaching the conclusion that God is just a conduit in which to temper the human experience, I have potentially butchered my own ego. I am less confident, less kind, more insecure, and more anxious about my place in life, and more concerned about loss than I likely would be if I were as strong enough to accept a way of thinking that is infinitely times larger than me, unless it appeared in front of me (in all my self-importance) and made itself demonstrable.

Yet, in successfully abandoning God, I have also successfully abandoned humanity’s oldest, most useful means for allowing one's self to proceed further in a world that they are fundamentally not meant to thrive in.

My own thoughts hinder me.

And so, the idea that Kai has been given a cognitive choice whether or not to erase Marie from the world or to sustain the prosperity of his own family is rather significant. It is also likely the way in which the author inserts his own thoughts regarding a paradox existing between living with faith or living strictly within materiality. I think they reinforce the validity of both choices by emphasizing that the world protected by Marie, despite its constraints placed upon technology for the purpose of preventing conflict, is a valid form of existence that is accompanied by legitimate human perseverance.

That, to me, is the most profound thesis of “The Music of Marie”. That there is no wrong choice for us to make. A more justified “truth” is purely subjective, only differentiated by what we understand the “point” of life to be, and how suggestive that leaves us to willingly opening Pandora’s Box. Both living in pursuit of faith and living by one’s own individual conviction leads us to our own truths.

While it is unlikely that the concept of religion will dissipate entirely for as long as mankind doesn’t become extinct, an increase in the quality of living for most nations in recent eras, combined with technology that is capable of power that rivals those described by Gods in ancient scripture, has definitely resulted in a decrease in the reliance on faith by most people (probably even more so since this was first published in 1999).

One wonders if we’ll eventually reach a monastic singularity - where we have to make a decision whether or not to embrace religion wholeheartedly as our universal truth, or discard it entirely. One wonders what we would gain from each parallel future.

And what would we lose?

Thanks for reading!